We grow and change all our lives from the time we are born. But as babies we have little sense of being a separate entity from our mothers, but then we are given a name and the individual begins to have a status as a separate being.

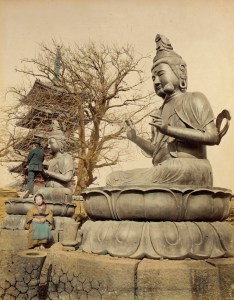

Frederic Edwin Church

Years ago, I was lucky enough to meet the writer Jean Liedloff, who had written a remarkable book called The Continuum Concept. While exploring the South American forests, she became separated from her party and guides and was rescued by a group of indigenous people who looked after her until they could return her to ‘civilisation’. Being a sociologist, she began studying their ways and noticed the remarkable resilience of the children. She discovered that they never left the physical presence of their mothers for at least the first year of their lives. By the age of six or so they were so calm and secure, that they could go hunting with their fathers. By contrast, the children who had been taken away to be educated by the missionaries never seemed to display this security, because their continuum had been broken, and the problems of so-called advanced societies had begun.

With a name and this sense of separation, a rather erratic picture of ourselves begins to form, known in Pali as sakkaya-ditthi (personality view).

As we grow and surrender the instinctive security of childhood, we begin to build up new defences against the outer world we are coming to know, and the safety of childhood (if we are fortunate) is replaced by the seeming security of the individual. Then, as this proves only partially adequate, we look for other protections and other solutions, physical or psychological. This growing and changing often causes turmoil of one kind or another and so we seldom if ever have a moment to give attention to the quiet awareness that underlies everything and is unaffected by the mass of little successes and disasters that occur, if indeed we ever noticed it amongst all the distractions we are prey to.

We keep having to rescue our persona (‘persona’ is Greek for ‘mask’) with its loves, hates and desires, from all the problems it encounters, and often even to rebuild it if severely damaged, unaware that there is a quiet watcher that has been a sure refuge all the way through.

The Buddha also stressed the value of being with good people and the warmth they provide as we struggle with our various problems, often unaware of their causes; and without this, our lives can be much diminished. Too often, in search of gain, we often lose that which is most precious. We need a quiet space in which the awareness can breathe and renew us, as it will, and recharge us when our batteries are low. This is where meditation is most valuable, not simply as a practice, but a renewal of being.

For, instead of being fully in our environment, we invest in the bits that interest us and ignore — or try to change — the rest, unaware of our mutual interdependence. I often watch people walking from place to place and how little they take in of the world around them. When I see people speeding past, I often see from their body posture that they are not in a hurry, but are probably speeding along because somewhere ahead, it is more interesting or promises something. Recently I was watching a dazzling sunset, when two young men went past gazing at their mobiles. I pointed out the wonderful view, and for a moment, their eyes drifted to the sunset, unseeing, and then back to their mobiles. I confess to feeling a slight sadness. A woman I spoke to later said: ‘But they don’t really look at anything, do they these days,’ and I regretfully had to agree. Perhaps if they did, they might see the lilies of the field, of which Jesus spoke, and realise that they outshone even the glory of the internet. And this is part of the joy of children discovering that the world is full of wonderful things waiting to be discovered. And what we discover in this way is part of our sense of being.

As a boy, I went to a country school, and the headmaster, who was an entomologist, used to take us on regular nature walks through the countryside, and to this day I am very grateful for his way of opening up the natural world to us. Everything came alive for us, and to me, it still does.

Images:

Heart of the Andes Frederic Edwin Church American 1859

This picture was inspired by Church’s second trip to South America in the spring of 1857. Church sketched prolifically throughout his nine weeks travel in Ecuador, and many extant watercolors and drawings contain elements found in this work. The picture was publicly unveiled in New York at Lyrique Hall, 756 Broadway, on April 27, 1859. Subsequently moved to the gallery of the Tenth Street Studio Building, it was lit by gas jets concealed behind silver reflectors in a darkened chamber. The work caused a sensation, and twelve to thirteen thousand people paid twenty-five cents apiece to file by it each month. The picture was also shown in London, where it was greatly admired as well.

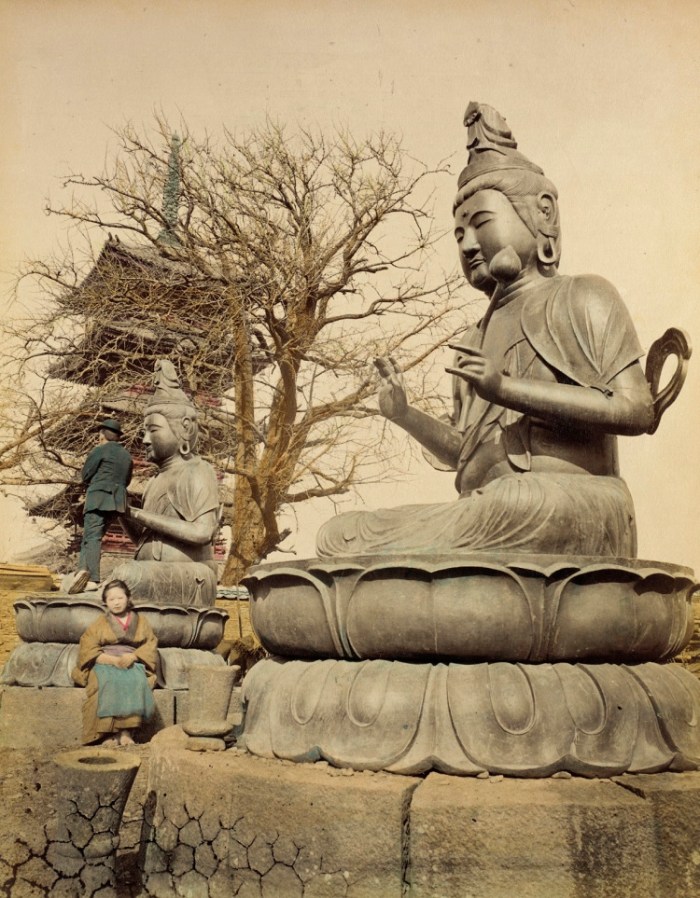

Bronze Buddhas. 1865 Photograph, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA)

See: Buddhist Photographs of Japan in 1865

You can see many more of these wonderful photograph on the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) website.

Thank you. I read post every day. I am grateful for the encouragement.