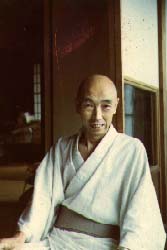

I’m sitting on my cushion in the morning before going to work and that feeling of openness comes, — not a thought-free feeling but one of awareness of being there, on the cushion, and of being content with just that. Then there is a feeling of gratitude for being taught a zazen with no strings attached—no elaborate initiation, no progress reports, and no conclusions. But there is a personal mystery that shrouds my feeling of gratitude. Why have I felt such ambivalence for the man who introduced me to and guided me through this practice? I feel that I must contact him again and work through these feelings and put some kind of closure to our relationship. The man is Uchiyama Kôshô Roshi and he was abbot of Antaiji from the time of his teacher’s death in 1965 until his own retirement in 1975. During his ten years as abbot of Antaiji, Uchiyama set up a temple where clergy and lay people, Japanese and westerners, men and women, could practise zazen together in as accommodating an atmosphere for practice as one can imagine in a temple in Japan.

So why the ambivalence?

It’s fall of 1970. Lunch is over and the monks, three lay western students including myself, and Roshi are sitting on the verandah relaxing. Roshi is looking at a book on origami (Japanese paper folding) given to him by one of the monks. Some conversation ensues and Roshi gets up and goes into his room. A few minutes later he comes out with a bunch of little paper folded animals. More conversation, none of which we relatively recently arrived westerners understand, and then, through Dôjin, a disciple who speaks a little English, Roshi brings us into the conversation.

Roshi holds up the book and shows us the instructions for folding a pig. Through Dôjin he says to us, ‘To make this pig, two pieces of paper.’ Then he picks up his own beautifully folded pig and says, ‘This, only one paper.’

The monks laugh what feels to me to be a bit of a nervous laugh. I smile. Then a rat from the book is shown, followed by two of the Roshi’s beautifully folded silver and gold rats. Again the same spiel: the book shows how to make it with two pieces of paper and the Roshi points to his and says, ‘Only one piece,’ and what I imagine to be some more nervous laughter. The reason the rats are silver and gold is that Roshi was born in the year of the rat. Then a few more animals are brought out and a similar discussion follows and then Roshi brings all the animals back to his room. Everyone disperses and I sit there thinking that roshis should act more humbly.

It’s spring of 1974 and I’m in Roshi’s room and the talk comes around to Sodô san, Roshi’s older brother disciple of Sawaki Roshi. Sodô san sits by himself in a town called Komoro in the Japan Alps of Nagano Prefecture. He composes poems and songs, produces beautiful calligraphy, plays songs he composes on the leaf, and sits zazen, usually alone, in a corner of Kaikoen Park in Komoro. He has one disciple whom he accepted reluctantly. The disciple works in a miso factory in town while Sodô san does his work of playing the leaf for travellers who pass by his spot during the day. I’ve watched these two old teachers tease each other when they’ve got together at memorial ceremonies for their teacher Sawaki Roshi and I’ve felt a mutual warmth when they got together at those times. So when I suggest to Roshi that Sodô san has the true spirit of Bodhidharma, I am a bit taken aback when his response is, ‘I believe I have more of the spirit of Bodhidharma then he does.’

After Roshi’s retirement from Antaiji, I visit him several times at various homes that were lent to him by people who are in some way connected to him, lay disciples perhaps. The conversation is lively and friendly and relaxed. However, I usually sense in his remarks some insecurity that I didn’t believe a ‘roshi’ should have. He would say how he always said he would make history or some other very ‘un-roshi’ type thing.

But here I am sitting in my room feeling nothing but gratitude for this man who was my teacher during my seven years in Japan, for whom I am expressing these misgivings. When I add up all the remarks Roshi has made that I have felt disappointment over because they don’t fit with my expectations for a ‘roshi,’ they might add up to a short afternoon conversation. . And they all refer to things that might be considered quirks in his personality, if my perceptions were accurate. What was happening all the rest of the time? What was Roshi doing and teaching us during our stay at Antaiji?

He set up Antaiji Temple as no other temple in Japan—as a place to support sitting with as few frills as possible. He sat with us during all the sesshins, teaching us through doing rather than talking. He lectured, but never during sesshin. He met with us individually, but there were no formal meetings during sesshin. The reason he gave for this diversion from the traditional teaching was that he didn’t want to disturb his own zazen. Was this a selfish statement or just another affirmation of his belief in zazen? He never sat facing us as most other teachers did. He faced the wall as we did, and his head sometimes bobbed as did ours. And he told us to look at zazen and not at him as our teacher. It’s almost as if he knew some of us would become disappointed in him and he didn’t want our disappointment to carry over into our zazen.

Sesshins at Antaiji were unlike any others I have experienced in Japan or America. No one was ever turned down from joining the practice for lack of space or lack of funds. A temple that could comfortably hold about thirty people, Antaiji would swell up to accommodate over one-hundred people on occasion. I’m reminded of the ‘Farmer Gray’ animation I watched on TV as a kid. The mice used to go on picnics after emptying Farmer Gray’s house of cheese and other goodies. Then they would get in a tiny bus, hundreds of mice. As they got into the bus in great numbers the bus would start to swell up many times its original size. When the mice got to the picnic grounds, they would pour out of the bus and it would shrink down almost to nothing. That’s what happened at Antaiji sesshins, especially the ones around the new year.

Japanese people traditionally go to pray at temples and shrines over the new year. Those who practise zazen like to sit over the new year. Many are working people who can’t leave their jobs to sit a whole sesshin. The new year sesshin would start two days before the new year and end two days after. On December 31st people would start pouring into the temple ready to sit and spend the night. The zendo would fill with rows and rows of people covering every inch of floor space. Cushions would appear and people would make room so that all of the space was used. A guest sleeping room which could accommodate eight to ten sleeping mats would sometimes have over twenty people sleeping in it. People who never saw each other before were squishing their bodies together to make room for newcomers who seemed to keep coming. All this done in relative silence. It was the strength of this one man and his will to make a place where all could practise that made it possible.

Uchiyama Roshi had an independent spirit and he wanted his students to develop that same independent spirit. He clearly saw the danger of students looking for an authority to tell them how to be; of how they flounder when their teacher is no longer there for them. I’m sure this was brought home to him in his relationship with his teacher. It was his teaching an independent practice, one which needed neither teacher nor support group but could accommodate both, that I learned to appreciate most. You could find no excuse not to sit other than that you didn’t want to. And it was my appreciation of this practice that made me feel that I wanted to thank Uchiyama Roshi.

I had visited Japan at least five times in the last seven years and always managed to avoid visiting him. I think that I didn’t want to muddy my good feeling for an old teacher by a conversation that might bring back disappointment. I was afraid of being disappointed by the man who warned us all that if we depend on anybody other than ourselves we will be heading for disappointment. I felt that I understood that lesson when I had the time to put it into perspective, but had I learned it well enough to feel it in the moment? Anyway, I wanted to tell him what I was feeling and I mentioned so in a letter to Tom Wright, a friend of mine and a long-standing disciple of Uchiyama. This was the Winter of 96. Tom responded, saying Roshi was dying and probably wouldn’t regain enough awareness to read a letter if I wrote to him.

That spring Roshi miraculously recovered. I was visiting Japan the following summer and made plans to visit him when Tom and another disciple were scheduled to visit. Some business got in the way and I couldn’t make it that day. I started to wonder whether I would make this another visit to Japan in which I would avoid seeing him. I was writing a story about my years at Antaiji when Uchiyama was abbot and knew I had to see him. But mostly I wanted to thank him for the precious practice he taught me.

One day on my way back to my Japanese home in Osaka, I found myself about an hour away from Shiojiri, a small town where Roshi spent his summers to escape the heat of Kyoto. I picked up the phone and called. His wife Keiko answered,

‘Hello.’

‘Hello, this is Arthur. I studied at Antaiji when Roshi was there. We’ve met several times since Roshi’s retirement.’

‘Yes, I remember you. How are you?’

‘Fine, thank you. I called to make an appointment to see Roshi. It’s already late, so another day would be fine.’

‘Where are you?’

‘I’m at Nagano station.’

‘That’s less than an hour from here. It’s only four o’clock. Please come now. Roshi has spent the day in bed. When visitors come it gives him energy.’

‘O.K., I’ll come right over.’

Keiko gave me directions and with feelings of excitement and anxiety I started on my way to their house. I don’t really know why the anxiety was there. Uchiyama Roshi has always been a warm host and a lively conversationalist. It must have been the old ambivalence aroused and the ensuing guilt that made me apprehensive. But the excitement of seeing an old teacher and friend predominated as I made my way to his house. Shiojiri like so many Japanese towns was dense with houses and stores that looked much alike and I got lost twice. I finally made it to his house with the help of a friendly citizen of the town. Keiko met me at the door and led me to a room adjacent to a verandah. The verandah faced a small Japanese garden with a pond, pine trees, patches of moss and some shrubs. We were shaded from the sun and a cool late afternoon breeze made the spot quite pleasant. Roshi was just getting out of bed and Keiko brought me a cool drink and asked me to make myself comfortable while I waited. I gave her some cakes I had picked up at the Shiojiri station and sat down and enjoyed the breeze and the view.

Roshi was now eighty-five years old; he had had failing health for the twenty-eight years I had known him. He was a frail man all his life who looked as though a good wind would knock him over. I hadn’t seen him in over seven years. When he joined us, I was shocked at how much he’d aged. Jôkô, a one-time disciple of Roshi, whom I had visited a week before my visit to Shiojiri, and who had recently visited Roshi, warned me that he’d aged, but I was still surprised. Most of his teeth were out, he had a special hearing device that he carried in his pocket, and walking was difficult for him. But when he began to talk, a youthfulness I remembered well took over.

‘It’s been a long time, Arthur, How are you?’

‘Yes it has. I’m fine. How have you been?’

‘I’m okay now. I died once but I’ve come back.’ (Roshi laughs) He continued describing a period of about a month, the previous autumn, when he lay in bed barely conscious.

I wanted to ask him about old Antaiji and his relationship with Sodô san and Ikebe Sensei, two teachers and friends of his whom I was writing about. But it became clear pretty soon that he wasn’t interested in talking about old friends or bygone years.

‘Roshi, when we were training at Antaiji . . .’

‘I’m not interested in the past,’ he cut me off. ‘I’m interested in the future, which for me means death. I could die at any moment. I did die once,’ he repeated. ‘The fact that I could die at any moment interests me greatly.’

‘I remember the first talk I ever heard you give. It was in 1970. What stood out in my mind then was what you said about death. You said you might die tomorrow or you might live many years, but it was all the same.’ I wasn’t consciously attempting to bring him back to that period, but had I, it wouldn’t have worked.

‘I’ve spent my life talking about death,’ he said and continued, ‘But never with the understanding and immediacy I feel now.’

There was no morbidness in what he said or in the way he said it. It was truly the wonder of a new awareness and a new nearness to death.

‘Since life and death are one and the same, my life is rich for my understanding of death.’

He paused for a moment and then continued, ‘The zazen I did most of my life has prepared me for old age. Old age is constant zazen. Most people have difficulty with old age because they are experiencing it for the first time. They haven’t experienced it in youth, as I have through zazen.’

He repeated over and over that zazen and old age were the same.

‘I wish my father had your spirit with regard to death.’

‘Let me get you something I wrote recently about dying. Please give it to your father.’

Keiko served the cakes and we started eating them. I became concerned whether Roshi, with his two remaining teeth, would be able to eat them, but he was champing away.

‘These cakes are very good Arthur.’

‘I bought them at the Shiojiri Station. The woman behind the stand said you would like them.’

I talked a bit with Keiko about Kyoto, where she grew up, and listened to her lament having had to live away from the old capital in order to be with Roshi, how she missed her friends and family there. It was a bit like talking to someone from ancient Japan, during a period when exile from the capital was a fate worse than death. Then she went away, either into the kitchen or the garden to do some work. Roshi talked about a recent TV appearance he made and how he spent most of the programme talking about death.

It was getting dark and I thought I should prepare to say goodbye. A man named Shimizu who I gather donated this house to Roshi for the hot summer months usually dropped by after work to have a few words. After talking a bit with Mr. Shimizu, Roshi would retire. It was a little routine Roshi must have become accustomed to.

‘I wonder why Shimizu hasn’t come yet?’ Roshi muttered to himself.

Then a few minutes later, ‘Keiko, Mr. Shimizu hasn’t arrived yet?’

‘Not yet.’

‘He’s usually here by now.’ Roshi spoke half to himself and half to me.

I started rehearsing my goodbyes. ‘You must be tired Roshi, so I’ll take my leave.’ or ‘Thank you for taking the time to talk with me. It’s getting late and you must be tired.’ And then I wondered if I should wait a little longer for Mr. Shimizu to show up. But nothing came out of my mouth.

Roshi then turned the conversation to a fellow, one of his first American students, who had recently come to Japan to visit him after moving to Hawaii. This man came every day for almost a month to see Roshi and be of help in however he could.

‘Arthur, do you know that fellow Fred?’

‘I know the name and a little about him. He came to Antaiji a year before I did.’

‘He visited me recently. He would come every day and give me wonderful massages.’ Roshi stared out into the garden and then, perhaps feeling ready to retire, looked around and said, ‘Where is Mr. Shimizu? . . . Keiko, Mr. Shimizu hasn’t come yet?’

‘Not yet.’

‘He’s quite late isn’t he? Maybe he’s not coming.’

I thought I’d better thank him and leave, but I couldn’t say anything. Then I mumbled it was getting late and perhaps I should leave but I don’t think he heard me. The next moment Roshi said, ‘I guess Mr. Shimizu isn’t coming. You had better go now Arthur, I’m getting tired.’

The realization that it was time for me to leave was in both our minds but Roshi had a much easier time expressing it than I did. Roshi and his wife saw me off at the door, thanked me for coming and asked me to come again. We bowed to each other and I walked quickly to the train station.

On the train back to Osaka I thought about our meeting. I was uncomfortable some of the time, but in no way did Roshi make me uncomfortable. He was gracious as ever and still full of life. I came with all kinds of questions and didn’t get a chance to ask any of them. My main purpose, I thought, was to thank him for the years of teaching and to let him know that I now, after 28 years, see the true wisdom in his approach to zazen. Then I realized that if I really understood what he was saying all those years, I would also realize that my intentions before seeing him weren’t very important. But seeing him was. He is very human and he never stopped letting us know that. Many times he told of how his teacher, Sawaki Kôdô Roshi was misunderstood because he had a very charismatic personality and people were impressed with his charisma and missed his Buddhism. Uchiyama Roshi had the most profound approach to Buddhism that I have ever encountered. But I was so caught up with his personality that I was missing his Dharma. In a very subtle way he was reminding me of my tendency to let his personality get in the way of his Dharma. His personality was not bad—he was charming, funny, interesting and a good host. But he wasn’t perfect and as long as I probed his personality instead of just listening to his teaching , I would find some imperfection. I am reminded of Roshi’s remarks about his teacher Sawaki Roshi in an interview about a month before Uchiyama’s death. He said:

‘Sawaki Roshi was not my “true teacher”. Sawaki Roshi, too, was a bombu (a deluded person).’

This statement taken out of context might make one feel that he was ungrateful to the man he studied under for over twenty-five years.

He added, however, ‘I’ve always told my disciples that the true teacher is inside each of them and that they should search for him there.’

I believe that he saw the danger when one idolizes another, as he may have done at some time with his teacher. Perhaps he wanted to prepare his students for the fact that we are all basically alone. And I might add, we can help each other in our aloneness, and that is where we are connected. When Uchiyama Roshi faced the wall during sesshin, neither lecturing nor holding private meetings, he was giving us his most profound teaching. Do zazen, depend on nobody and I too will join you in this practice.

On March 14th, I received a call from one of Roshi’s disciples, Dôyû Takamine, saying the master died peacefully in his sleep the previous day. A week later my friend Michael Hofmann another old Antaijiyte wrote telling me about the funeral.

. . It was the start of the last zazenkai (March 14) that Doyû informed us of Uchiyama Roshi’s death. Doyû and his wife Hideko went to Uji and spent the night there.

It seems Roshi had a sense his death was coming and had been making some final preparations during the previous week. The day of his death he had been up and around . . .

The funeral was Monday, the 16th, and the ceremony took place inside his house with about forty people in the room and another forty standing outside.

You would have recognized most of the monks—the twenty-five years since most of them had been together slipped away, they all seemed like unsui (floating clouds), keeping in the background (some even wearing samue, monk’s work clothes), but allowing everything to move along with dignity and great feeling. Kôhô san (the head monk) never left Uchiyama Roshi’s wife’s side.

The brief ceremony ended with a period of zazen and then three bows. Roshi’s open casket was brought out to the veranda and everyone formed a line to place a flower on his body and make a final bow . . .

This article first appeared in Buddhism Now.

Other posts by Arthur Braverman

Categories: Arthur Braverman, Chan / Seon / Zen, Encyclopedia, History, Mahayana

I appreciate this profound and subtle teaching that he was finally able to realize from his teacher. Thank you for this sir.

Great article, thanks!

Thank You 4 sharing. Gassho