During a conversation with a psychologist friend, he said: ‘Sympathy is a natural response between human beings, but is sometimes blocked by fear of rejection or the influence of dominant parents who regard it as a weakness, but it underlies so much of our human relationships.’

I often think of the account of the Chinese pilgrim Hsiuen Tsang (seventh century), who journeyed for many years throughout the far east, seeking Buddhist communities and lost scriptures to bring back to China. One of the places he visited was the great lake of Issik-Kul, which runs for a hundred miles through the mountains of Kirghizstan, and is bordered by the Heavenly Mountains (the Tian Shan).

Here, the Great Khan of the Mongols held his summer camp, and little fawns under the specific protection of the Khan, wandered about the camp, being fed titbits by his men. Hsiuen Tang described the event in some detail and the grace with which the Khan treated him as a guest.

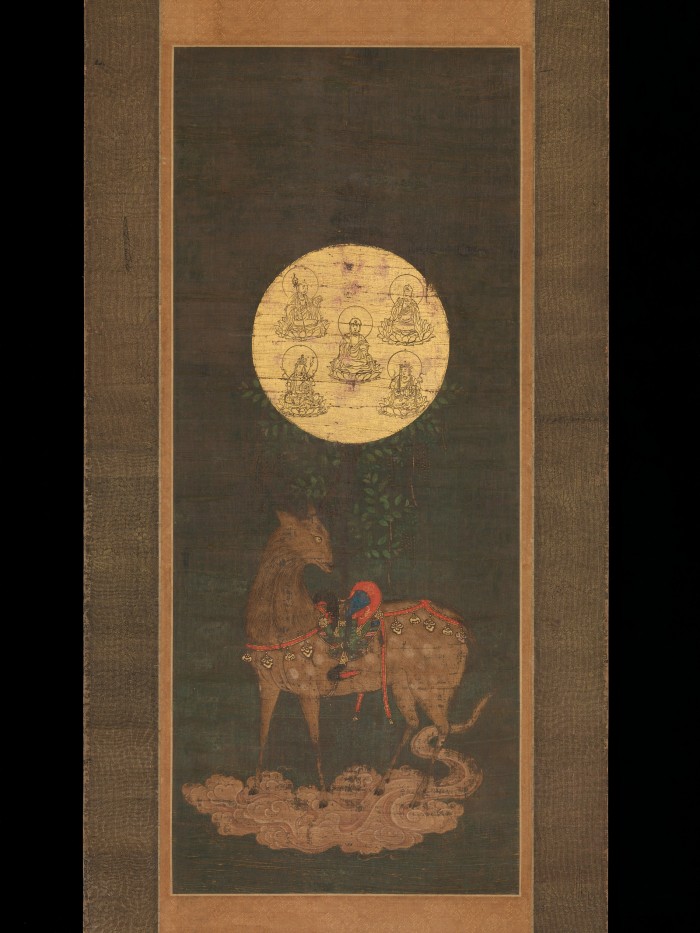

Deer Mandala of the Kasuga Shrine (Kasuga Shika Mandara)

Sympathy is — as the dictionary tells us — ‘Sharing in the emotions of others, especially the sharing of grief, pain etcetera; a feeling for the ills and difficulties of others and a mutual liking resulting from an affinity of feeling,’ as with Hsiuen Tsang and the Great Khan, but in that openness, also come the responses to joy and happiness.

‘I know he was a barbarian — but I did like him,’ Hsiuen Tsang confessed. It was the grace and kindness of the reception that touched him and that he remembered.

While sympathy is often blocked by anger or fear of rejection, sympathetic joy is often blocked by jealousy or greed — wanting what the other has — whether happiness, possessions or fortune. I remember once envying the poise of a young man being introduced to the firm by the chief clerk, because his father was one of the directors. And on another occasion, I remember a large, black limousine drawing up at the quay in Exeter, and a family stepping out; and I envied the prosperity they exuded, compared to my rather penurious existence, but on the whole I am grateful to how rarely I have felt like this, and in the meantime I am grateful for how friends and acquaintances have shown me the value of so many things — and people around me.

I remember my cousin, who had many advantages I never had, but I never envied him and welcomed his successes, because by then I had realised that we all have the same basic problems to face and our sympathy for others helps not only them, but ourselves to cope with our humanity.

Sympathetic joy is not bound by give and take, it is founded on compassion and one can find compassion for the most successful as well as the least, because their human problems are the same. If we see our own problems softened and perhaps made manageable by sympathy and kindness, this can spread to the understanding of the unhappiness of others, and in helping them, the joy that underlies our own response can spread to the reinvigoration of the little things that bring us all joy and happiness.

Click here to read more articles by John.

Read other teachings on the ‘Four Immeasurables’ here.

Images:

Deer Mandala of the Kasuga Shrine

Japan late 14th century

By the fourteenth century, tendencies toward the synthesis of Buddhism and Shinto led to the belief in Shinto kami as manifestations of Buddhist deities. The deer, vehicle of the deity Takemikazuchi, rides on a cloud and wears a colorful saddle that supports an evergreen sakaki tree interlaced with wisteria vines. At the tree’s canopy is a golden mirror that includes images of the five Buddhist deities associated with the kami of the Kasuga Shrine in Nara.

With thanks The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Categories: Everyday Buddhism, Foundations of Buddhism, John Aske

Comments